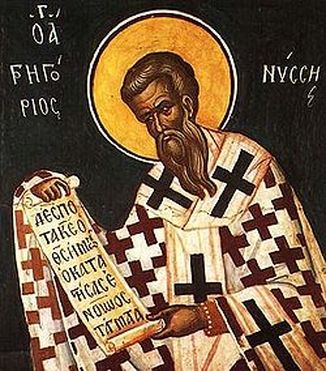

St. Gregory of Nyssa (330-395 A.D.)

The Fathers of the Church spread the gospel of Jesus Christ, defended the Church in apologetic writing and fought the many heresies of the first six centuries of Christianity. These men, also called Apostolic Fathers, gave special witness to the faith, some dying the death of a martyr. Like Jesus who referred to Abraham as a spiritual father (Luke 16: 24) and St. Paul, who referred to himself in the same terms (1 Corinthians 4: 15), the Fathers were zealous for the word of God. Their writings are a testimony to the faith of the early Church, yet many Christians are unfamiliar with the work of Clement of Rome, Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp of Smyrna, Justin the Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Cyprian of Carthage, Athanasius, Ephraim, Cyril of Jerusalem, Hilary of Poitiers or Gregory the Great to name of few of the early Fathers. Periodically we will provide biographical information and examples of the writing of these great men of faith. This page will focus on the St. Gregory of Nyssa.

St. Gregory of Nyssa (about 330-395 A.D.) He was born in Cappadocia, Asia Minor, a member of remarkable family that included St. Macrina the Younger and St. Basil the Great, his older sister and brother. Both Basil and his other brother, Peter, became bishops. He started his career as a teacher of rhetoric and married, but was subsequently persuaded by his brother Basil and his friend, St. Gregory of Nazianzen to become a priest (married clergy were allowed at that time). He was selected Bishop of Nyssa (a town between Caesarea and Ancyra) in 372 A.D. through Basil's influence in an effort to develop allies in the struggle against the Arian heresy, which denied that Christ was God. A letter of St. Gregory of Nazianzus, consoles him on the loss of Theosebeia (presumbably his wife), whom he had continued to live with, but as a sister, when he was ordained a bishop. About 376 A.D. he was deprived of his see by the Emperor Valerian, who was persecuting Christians. He returned to his see to the great rejoicing of the people in 378 at the death of Valerian.

After St. Basil's death in 379 A.D., Gregory became the leading theologian in the East. Elected Bishop of Sebaste the year before, he played a leading role at the ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 381, which condemned the Arian, Eunomian (Anomean), Sabellian, Marcellian and Pneumatomachian heresies (which generally tried to deny the divinity of Jesus and/or the Holy Spirit), reaffirming the Nicene Creed of the first ecumenical Council which had been held at Nicaea in 325 A.D. Like St. Augustine, he is both a philosopher and theologian as well as a mystic. The Emperor Theodosius designated his see one of three in the East to be centers of Catholic communion. Known for his oratory skills, he preached the funeral oration for the imperial princess, Pulcheria, and later, for Empress Flaccila at her death in 385 or 386.

Perhaps his most well known treatise was entitled "Virginity" which, like St. Paul, extols the virtue of this way of life. His Great Catechism, quoted below, shows his view of the Eucharist, which like other early Church Fathers, confirms the Real Presence of Christ in what was formerly mere bread and mere wine. Gregory writes that man becomes what he eats. Using metonymy, the body is the bread and wine it consumes. This was the case with Jesus, the incarnate Word as He assimilated bread and wine in his days on earth, so too He now assimilates the Eucharistic offering [the thanks offering at the Mass] and gives what has become Himself through assimilation [by action of the Holy Spirit]. In this manner he passes on to us the immortality that is proper to his risen, glorified Body. Gregory uses the word "transelements" which in the Greek means a restructuring of the elements [of bread and wine, in this case, into the Body and Blood of Christ]. Later, western theologians used the word "transubstantiation" to describe this mystery, meaning "to change the substance" [of what had been bread and wine].

The Great Catechism [383 A.D.]

1030 [8] "Since both the soul and body have a common bond of fellowship in their sharing in the misfortunes which derive from sin, so too is there a certain analogy of corporeal [bodily] death to that death which is of the soul. Just as in reference to the flesh we pronounce that death which is a cessation of sentient life, so to in regard to the soul we term that death which is separation from true life [God]."

1031 [11] "If you inquire how divinity is conjoined to humanity, you will have first to inquire as to what the coalescence is of the soul with the flesh. If you do not know the manner by which your soul is united to your body, do not imagine that that other question needs to be understood by you either. . . . Yet the miracles recorded do not permit us to doubt that God was born in the nature of a man."

1034 [31] "Some are saying that God, if He wanted to, could by force bring even the disinclined to accept the kerygmatic message [the Good News of Christ]. But then where would their free choice be? Where their virtue? Where their praise for their having succeeded? To be brought around to the purpose of another's will belongs only to creatures without a soul or irrational."

1035 [37] "But since human nature is twofold, composed of body and soul, it is necessary that both of these make contact with the Author of life

. . . What then is the remedy [for the body tainted by sin]? it is none other than that Body that has been shown to be stronger than death [Christ's], and has become [the source] of life for us. Just as a little yeast, as the Apostle says [1 Cor 5:6] --assimilates the whole batch of dough to itself, so that body raised by God to immortality, when it enters our bodies, changes [Gr., metapoiei] and transforms them [Gr, metatithesin] into itself. . . . Since only the body in which the Divinity became incarnate has received the grace [of immortality] and since it has been demonstrated that it is not possible for our body to become immortal, unless it share in incorruptibility through communion with the Immortal Body, it is necessary to consider how it is possible for that one Body, although it is distributed continually to so many thousands of the faithful throughout the world, to remain whole when it is allotted to each individual, through a portion while still remaining whole in itself . . . .(8)... Since each body gets its existence from nourishment, from eating and drinking . . . . (9) so, if a person sees bread, he sees, in a certain sense, the human body, because the bread that enters the body becomes the body itself. So too, the Body into which God entered, by being nourished with bread, was in like manner identical with the bread. . . . This Body, by the indwelling of God the Word, has been changed [Gr.,metapoiethe] to divine dignity. Rightly then do we believe that the bread consecrated by the word of God has been changed [Gr., metapoieisthai] into the Body of God the Word. For that Body was bread in power, but it has been sanctified by the dwelling there of the Word, who pitched his tent in the flesh. The change that elevated to divine power the bread that had been transformed into that Body causes something similar now. In that case, the grace of the Word sanctified that Body whose material being came from bread and was, in a certain sense, bread itself. In this case, the bread "is sanctified by God's word and by prayer" [1 Tim 4:5], as the Apostle says, not becoming the Body of the Word through our eating but by being transformed [Gr., metapoiumenos] immediately into the body by means of the word, as the Word himself said, 'This is my Body' . . . . (12). . . He shares himself with every believer through the Flesh whose material being [Gr., sustais] comes from bread and wine . . . in order to bring it about that, by communion with the Immortal, man may share in incorruption. He gives these things through the power of the blessing by which he transelements [Gr., metastoikeiosas] the nature of the visible things [to that of the Immortal]."

Sermon on the Day of Lights or on The Baptism of Christ [383 A.D.]

1062 [Jaeger: vol 9, pp. 225-226] "The bread again is at first common bread; but when the mystery sanctifies it, it is called and actually becomes the Body of Christ. So too the mystical oil [used in the sacraments of baptism, confirmation, and for the sick], so too the wine; if they are things of little worth before the blessing, after their sanctification by the Spirit each of them has its own superior operation. The same power of the word also makes the priest venerable and honorable, separated from the generality of men by the blessing bestowed upon him [holy orders--laying on of hands]. Yesterday he was but one of the multitude, one of the people; suddenly he is made a guide, a president, a teacher of piety, an instructor in hidden mysteries."

Sermon on the Interval of Three Days Between the Death and Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ or Sermon on the Resurrection of Christ [381 A.D.]

[Jaeger, vol. 9, p.287] "He offered Himself for us, Victim and Sacrifice, and Priest as well, and 'Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.' When did He do this? When He made His own Body food and His own Blood drink for His disciples; for this much is clear enough to anyone, that a sheep cannot be eaten by a man unless its being eaten be preceded by its being slaughtered. This giving of His Body to His disciples for eating clearly indicates that the sacrifice of the Lamb has now been completed."

St. Gregory of Nyssa (about 330-395 A.D.) He was born in Cappadocia, Asia Minor, a member of remarkable family that included St. Macrina the Younger and St. Basil the Great, his older sister and brother. Both Basil and his other brother, Peter, became bishops. He started his career as a teacher of rhetoric and married, but was subsequently persuaded by his brother Basil and his friend, St. Gregory of Nazianzen to become a priest (married clergy were allowed at that time). He was selected Bishop of Nyssa (a town between Caesarea and Ancyra) in 372 A.D. through Basil's influence in an effort to develop allies in the struggle against the Arian heresy, which denied that Christ was God. A letter of St. Gregory of Nazianzus, consoles him on the loss of Theosebeia (presumbably his wife), whom he had continued to live with, but as a sister, when he was ordained a bishop. About 376 A.D. he was deprived of his see by the Emperor Valerian, who was persecuting Christians. He returned to his see to the great rejoicing of the people in 378 at the death of Valerian.

After St. Basil's death in 379 A.D., Gregory became the leading theologian in the East. Elected Bishop of Sebaste the year before, he played a leading role at the ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 381, which condemned the Arian, Eunomian (Anomean), Sabellian, Marcellian and Pneumatomachian heresies (which generally tried to deny the divinity of Jesus and/or the Holy Spirit), reaffirming the Nicene Creed of the first ecumenical Council which had been held at Nicaea in 325 A.D. Like St. Augustine, he is both a philosopher and theologian as well as a mystic. The Emperor Theodosius designated his see one of three in the East to be centers of Catholic communion. Known for his oratory skills, he preached the funeral oration for the imperial princess, Pulcheria, and later, for Empress Flaccila at her death in 385 or 386.

Perhaps his most well known treatise was entitled "Virginity" which, like St. Paul, extols the virtue of this way of life. His Great Catechism, quoted below, shows his view of the Eucharist, which like other early Church Fathers, confirms the Real Presence of Christ in what was formerly mere bread and mere wine. Gregory writes that man becomes what he eats. Using metonymy, the body is the bread and wine it consumes. This was the case with Jesus, the incarnate Word as He assimilated bread and wine in his days on earth, so too He now assimilates the Eucharistic offering [the thanks offering at the Mass] and gives what has become Himself through assimilation [by action of the Holy Spirit]. In this manner he passes on to us the immortality that is proper to his risen, glorified Body. Gregory uses the word "transelements" which in the Greek means a restructuring of the elements [of bread and wine, in this case, into the Body and Blood of Christ]. Later, western theologians used the word "transubstantiation" to describe this mystery, meaning "to change the substance" [of what had been bread and wine].

The Great Catechism [383 A.D.]

1030 [8] "Since both the soul and body have a common bond of fellowship in their sharing in the misfortunes which derive from sin, so too is there a certain analogy of corporeal [bodily] death to that death which is of the soul. Just as in reference to the flesh we pronounce that death which is a cessation of sentient life, so to in regard to the soul we term that death which is separation from true life [God]."

1031 [11] "If you inquire how divinity is conjoined to humanity, you will have first to inquire as to what the coalescence is of the soul with the flesh. If you do not know the manner by which your soul is united to your body, do not imagine that that other question needs to be understood by you either. . . . Yet the miracles recorded do not permit us to doubt that God was born in the nature of a man."

1034 [31] "Some are saying that God, if He wanted to, could by force bring even the disinclined to accept the kerygmatic message [the Good News of Christ]. But then where would their free choice be? Where their virtue? Where their praise for their having succeeded? To be brought around to the purpose of another's will belongs only to creatures without a soul or irrational."

1035 [37] "But since human nature is twofold, composed of body and soul, it is necessary that both of these make contact with the Author of life

. . . What then is the remedy [for the body tainted by sin]? it is none other than that Body that has been shown to be stronger than death [Christ's], and has become [the source] of life for us. Just as a little yeast, as the Apostle says [1 Cor 5:6] --assimilates the whole batch of dough to itself, so that body raised by God to immortality, when it enters our bodies, changes [Gr., metapoiei] and transforms them [Gr, metatithesin] into itself. . . . Since only the body in which the Divinity became incarnate has received the grace [of immortality] and since it has been demonstrated that it is not possible for our body to become immortal, unless it share in incorruptibility through communion with the Immortal Body, it is necessary to consider how it is possible for that one Body, although it is distributed continually to so many thousands of the faithful throughout the world, to remain whole when it is allotted to each individual, through a portion while still remaining whole in itself . . . .(8)... Since each body gets its existence from nourishment, from eating and drinking . . . . (9) so, if a person sees bread, he sees, in a certain sense, the human body, because the bread that enters the body becomes the body itself. So too, the Body into which God entered, by being nourished with bread, was in like manner identical with the bread. . . . This Body, by the indwelling of God the Word, has been changed [Gr.,metapoiethe] to divine dignity. Rightly then do we believe that the bread consecrated by the word of God has been changed [Gr., metapoieisthai] into the Body of God the Word. For that Body was bread in power, but it has been sanctified by the dwelling there of the Word, who pitched his tent in the flesh. The change that elevated to divine power the bread that had been transformed into that Body causes something similar now. In that case, the grace of the Word sanctified that Body whose material being came from bread and was, in a certain sense, bread itself. In this case, the bread "is sanctified by God's word and by prayer" [1 Tim 4:5], as the Apostle says, not becoming the Body of the Word through our eating but by being transformed [Gr., metapoiumenos] immediately into the body by means of the word, as the Word himself said, 'This is my Body' . . . . (12). . . He shares himself with every believer through the Flesh whose material being [Gr., sustais] comes from bread and wine . . . in order to bring it about that, by communion with the Immortal, man may share in incorruption. He gives these things through the power of the blessing by which he transelements [Gr., metastoikeiosas] the nature of the visible things [to that of the Immortal]."

Sermon on the Day of Lights or on The Baptism of Christ [383 A.D.]

1062 [Jaeger: vol 9, pp. 225-226] "The bread again is at first common bread; but when the mystery sanctifies it, it is called and actually becomes the Body of Christ. So too the mystical oil [used in the sacraments of baptism, confirmation, and for the sick], so too the wine; if they are things of little worth before the blessing, after their sanctification by the Spirit each of them has its own superior operation. The same power of the word also makes the priest venerable and honorable, separated from the generality of men by the blessing bestowed upon him [holy orders--laying on of hands]. Yesterday he was but one of the multitude, one of the people; suddenly he is made a guide, a president, a teacher of piety, an instructor in hidden mysteries."

Sermon on the Interval of Three Days Between the Death and Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ or Sermon on the Resurrection of Christ [381 A.D.]

[Jaeger, vol. 9, p.287] "He offered Himself for us, Victim and Sacrifice, and Priest as well, and 'Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.' When did He do this? When He made His own Body food and His own Blood drink for His disciples; for this much is clear enough to anyone, that a sheep cannot be eaten by a man unless its being eaten be preceded by its being slaughtered. This giving of His Body to His disciples for eating clearly indicates that the sacrifice of the Lamb has now been completed."