The Canon of the Old Testament

The word “testament” Hebrew (berîîth, Greek diatheke) in Old Testament primarily pertains to God’s covenant with the people of Israel from the time of Abraham. The Jews did not have a closed canon of Scripture in the first century AD. The Old Testament books were written between about 1000 and 50 B.C. They were divided into three divisions, namely the Hat-Torah, Nebiim, wa-Kééthubim, or the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings.

However, Bibles of Catholics and Protestants diverged during the Reformation as Martin Luther removed 7 books from the Old Testament (O.T.), including Tobias and Judith which were written originally in Aramaic, perhaps in Hebrew; Baruch, Ecclesiasticus and I Maccabees in Hebrew, while Wisdom and II Maccabees were certainly composed in Greek. [Also, seven chapters of Esther, portions of Daniel including the history of Susanna (Daniel 13) and of Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) were excluded]. These additional books are known as the Deutero-canon (or second canon by Catholics). Their exclusions from the Protestant Bible during the Reformation was based on a misconception.

At the conclusion of the war with Rome in 70 A.D. Jerusalem was destroyed along with the temple and many of their manuscripts.

Two decades later, the Council of Jabneh (Jamnia), a group of Jewish scholars, meeting about 90 A.D. with the permission of the Romans, set up a reconstituted Sanhedrin. Although they discussed several writings in the Septuagint that were then in doubt in the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures and rejected Christian writings, there is no evidence as Protestants later claimed, they rejected the seven books Protestants now call the “Apocrypha” (meaning hidden), although they did agree to make a new translation of the Septuagint. This was an anti-Christian translation designed to frustrate Christians who were using the Septuagint to convert Jews. Aquila, the author, for example, translated Isaiah 7:14 as “young woman” instead of the Septuagint’s version’s translation, “virgin,” because they did not like the implication of the verse, “A virgin shall be with child and bear a son.”

Thus, when Protestants like Norman Geisler, in his work, Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences (1995), claims the Jews had always rejected these books from their canon and had the authority to do so because they were “entrusted with the oracles of God,” he completely ignores the fact that these same Jews had rejected their Messiah and that the destruction of their temple was a covenant judgment prophesied by our Lord (Mark 13:2; Matthew 24:2; Luke 19: 44; 21:6). It is interesting to recognize that the Jerome Bible Commentary seems to agree noting:

Toward the end of the first century A.D. at Jamnia, they decided that their Bible consisted only of books written up to the time of Ezra, when prophecy was deemed to have ceased; and this criterion, though not applied uniformly, excluded the books of more recent origin which were on the whole less in accord with the Pharisaic outlook. the need for a decision was forced upon the Jews because of the growing controversies with Christians; and besides delimiting the Canon of Scripture they also not long afterward condemned the Greek Septuagint translation as inaccurate.(Introduction)

Although they immediately add that this was “not of course binding upon the Christians” and that, for a time, St. Jerome regarded them as noncanonical, but this was before the Church defined the canon of Scripture. This latter point is reinforced by the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church which says the Council of Jabneh was not even an “official” council and hence did not have the authority to make such a decision, even if you ignore the New Covenant Church and its authority, which obviously superseded that of the Old Covenant religion, which could no longer be practiced since there was no temple in which to conduct their sacrifices in any case. The dictionary cited above also notes that “The suggestion that a particular synod of Jabneh, held c.100 A.D. finally settled the limits of the Old Testament Canon, was made by H.E. Ryle, though it has had a wide currency, there is no evidence to substantiate it” (Oxford Dictionary, p.86)

Thus, even during the time of Christ the Jews did not have a closed canon, which only reinforces the Catholic understanding of the important role of "the living and infallible Church of Christ" and her Oral (Apostolic) Tradition under both covenants (i.e., Old and New). Some theologians are not even convinced that there was a council of Jabneh at all.

The Massoretic Text (MT) of the Old Testament or Hebrew version were maintained assiduously by the so-called Massoretes, who transmitted them faithfully and with great consistency. But the anti-Christian Jews at Jamnia were said to have collected only 22 to 24 books in Hebrew. The so called Palestinian canon or the MT, which contained 39 books, was not fixed until about 300 A.D. (“The Council That Wasn’t,” by Steven Ray, This Rock, Sept’04, Click Here) This is the canon Luther adopted and Protestants generally accept today, but Catholics embraced the Septuagint from the beginning because this was the Bible of the Christian community. In fact almost all of the quotations of the Old Testament in the New Testament are from the Septuagint version.

The history of the Septuagint is that it was a project begun in the great city of Alexandria about 250 B.C. by a group of seventy rabbis, who supposedly did their translations independently and when they were brought together all were found to be identical, convincing many of their inspiration (The Catholic Bible: Personal Study Edition, p. 217). The translations may have taken decades but what is clear is that this was the Bible of the Jews in the Diaspora and it was the Bible quoted by Jesus and the Apostles in the New Testament in 300 of 350 instances where the Old Testament was quoted. The other 50 are usually paraphrases of either the Hebrew or the Greek only. Moreover, it is important to note that at least the Ethiopian Jews, followed a different canon, which is identical to the Septuagint and includes the seven deuterocanonical books (cf. Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 6, p. 1147).

The early Christians used the Septuagint to evangelize the world and one of the most startling examples is the reference to the story of the heroic mother who was martyred after watching her seven sons tortured and put to death by a brutal king who tried to force them eat swine’s flesh in violation of Jewish law. This story from 2 Macabees 7 is cited in Hebrews 11: 35 and this is obvious from the fact that no comparable story can be found in the Massoretic Text (MT), which became the Protestant Old Testament. This is but one of a number of clear references to the deuterocanonical books in the New Testament. The Early Church Fathers likewise used the deuterocanonicals.

As Protestant scholar J.N.D. Kelly notes, “Quotations from Wisdom, for example, occur in 1 Clement and Barnabas. . . Polycarp cites Tobit, and the Didache [cites] Ecclesiasticus. Irenaeus refers to Wisdom, the History of Susannah, Bel and the Dragon [i.e., the deuterocanonical portions of Daniel], and Baruch. The use made of the Apocrypha by Early Church Fathers like Tertullian, Hippolytus, Cyprian and Clement of Alexandria is too frequent for detailed references to be necessary" (Early Christian Doctrines, 53-54).

Origen’s famous Hexapla consisted of six parallel columns which contained:

(1) the Hebrew of his day;

(2) the Hebrew text transliterated into Greek;

(3) Aquila revised Septuagint;

(4) Symmachus revised Septuagint;

(5) LXX (Septuagint)

(6) Theodotion (a revision of the Greek text of the Septuagint)

Unfortunately, it is no longer extant, but it shows that Origen, who headed the great Catechetical School at Alexandria, took all the translations into account in his studies and considered the deutero-canonical books inspired. It is also important to note that there were considerable differences, for example, the Massoretic Text of Jeremiah was 2700 words shorter than the Septuagint and there are significant differences in the text of chapters 10 and 23. In Esther 107 of the 270 verses in the LXX find no parallel in the MT (Anchor Bible Dictionary).

The massive and scholarly Protestant Anchor Bible Dictionary after acknowledging that mainline Biblical scholars have used the Septuagint to correct corruptions in the MT and that it was translated from Hebrew texts “not necessarily translated from a text accessible to us,” notes:

A second reason western scholars especially specialists in Christianity, should consider the LXX, is that it was the Bible of the early Christian Church. It was not secondary to any other scripture; it was Scripture. When a writer allegedly urged his audience to consider that all scripture given by divine ‘inspiration’ is also profitable for doctrine, it was to the LXX not the Hebrew that attention was being called. The LXX also provides the context in which many of the lexical and theological concepts in the NT can best be explained. Excellent syntheses of the relationships between LXX and NT have been made. Summaries and evaluations of these discussions and issues appear in Smith (1972 and 1988).

Martin Luther wrote in his commentary on John, “We are compelled to concede to the Papists that they have the word of God, that we received it from them, and that without them we should have no knowledge of it at all." Luther’s embrace of the so-called Palestinian canon was no doubt also driven by his new-found theology. Just as the Jews found the Messianic texts unpalatable, so too the reformers had their theology-driven agenda. Luther reject the Macabees because 2 Macabees 12:45-46 contradicted his denial of Purgatory when it says “...it was a holy and pious thought...” to make “...atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin.” This clearly shows the Jews believed in praying for the dead and suggests the dead might be purified of their sins, lending credence to the doctrine of purgatory which Luther had rejected.

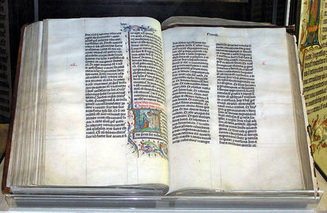

Perhaps we should conclude by remembering history, which tells us that not all Christians agreed on what was in fact inspired Scripture. Scriptural books were denounced by some as spurious and books that had no divine inspiration were sometimes considered to be inspired. Thus, it was and is critical to have an infallible authority to settle the canon of Scripture. This is the rationale for the councils of Hippo, Carthage and Rome addressing the canon issue. The canon of both the Old and New Testaments, was finally settled at the Council of Rome in 382, under the authority of Pope Damasus I. It had been used in the Old Itala or Vetus Itala, Latin Bible in use until the Vulgate of St. Jerome was published in 405 A.D.

Numerous Church Councils reaffirmed the Canon and it was not challenged until Luther’s actions in the Reformation. Catholics did not change the canon of Scripture to fit their theology but the Reformers did. It is well to remember that the Protestant myth that the Catholic Church supposedly added seven books to the Canon at the Council of Trent is still around and needs to be corrected by people who take the time and the trouble to examine the historical record. This is not difficult to do. Please examine your traditions to see if they are of men or of God. This is an essential distinction!

Need more convincing? Check out the writings of the Early Church Fathers on this topic by Clicking Here.

However, Bibles of Catholics and Protestants diverged during the Reformation as Martin Luther removed 7 books from the Old Testament (O.T.), including Tobias and Judith which were written originally in Aramaic, perhaps in Hebrew; Baruch, Ecclesiasticus and I Maccabees in Hebrew, while Wisdom and II Maccabees were certainly composed in Greek. [Also, seven chapters of Esther, portions of Daniel including the history of Susanna (Daniel 13) and of Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) were excluded]. These additional books are known as the Deutero-canon (or second canon by Catholics). Their exclusions from the Protestant Bible during the Reformation was based on a misconception.

At the conclusion of the war with Rome in 70 A.D. Jerusalem was destroyed along with the temple and many of their manuscripts.

Two decades later, the Council of Jabneh (Jamnia), a group of Jewish scholars, meeting about 90 A.D. with the permission of the Romans, set up a reconstituted Sanhedrin. Although they discussed several writings in the Septuagint that were then in doubt in the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures and rejected Christian writings, there is no evidence as Protestants later claimed, they rejected the seven books Protestants now call the “Apocrypha” (meaning hidden), although they did agree to make a new translation of the Septuagint. This was an anti-Christian translation designed to frustrate Christians who were using the Septuagint to convert Jews. Aquila, the author, for example, translated Isaiah 7:14 as “young woman” instead of the Septuagint’s version’s translation, “virgin,” because they did not like the implication of the verse, “A virgin shall be with child and bear a son.”

Thus, when Protestants like Norman Geisler, in his work, Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences (1995), claims the Jews had always rejected these books from their canon and had the authority to do so because they were “entrusted with the oracles of God,” he completely ignores the fact that these same Jews had rejected their Messiah and that the destruction of their temple was a covenant judgment prophesied by our Lord (Mark 13:2; Matthew 24:2; Luke 19: 44; 21:6). It is interesting to recognize that the Jerome Bible Commentary seems to agree noting:

Toward the end of the first century A.D. at Jamnia, they decided that their Bible consisted only of books written up to the time of Ezra, when prophecy was deemed to have ceased; and this criterion, though not applied uniformly, excluded the books of more recent origin which were on the whole less in accord with the Pharisaic outlook. the need for a decision was forced upon the Jews because of the growing controversies with Christians; and besides delimiting the Canon of Scripture they also not long afterward condemned the Greek Septuagint translation as inaccurate.(Introduction)

Although they immediately add that this was “not of course binding upon the Christians” and that, for a time, St. Jerome regarded them as noncanonical, but this was before the Church defined the canon of Scripture. This latter point is reinforced by the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church which says the Council of Jabneh was not even an “official” council and hence did not have the authority to make such a decision, even if you ignore the New Covenant Church and its authority, which obviously superseded that of the Old Covenant religion, which could no longer be practiced since there was no temple in which to conduct their sacrifices in any case. The dictionary cited above also notes that “The suggestion that a particular synod of Jabneh, held c.100 A.D. finally settled the limits of the Old Testament Canon, was made by H.E. Ryle, though it has had a wide currency, there is no evidence to substantiate it” (Oxford Dictionary, p.86)

Thus, even during the time of Christ the Jews did not have a closed canon, which only reinforces the Catholic understanding of the important role of "the living and infallible Church of Christ" and her Oral (Apostolic) Tradition under both covenants (i.e., Old and New). Some theologians are not even convinced that there was a council of Jabneh at all.

The Massoretic Text (MT) of the Old Testament or Hebrew version were maintained assiduously by the so-called Massoretes, who transmitted them faithfully and with great consistency. But the anti-Christian Jews at Jamnia were said to have collected only 22 to 24 books in Hebrew. The so called Palestinian canon or the MT, which contained 39 books, was not fixed until about 300 A.D. (“The Council That Wasn’t,” by Steven Ray, This Rock, Sept’04, Click Here) This is the canon Luther adopted and Protestants generally accept today, but Catholics embraced the Septuagint from the beginning because this was the Bible of the Christian community. In fact almost all of the quotations of the Old Testament in the New Testament are from the Septuagint version.

The history of the Septuagint is that it was a project begun in the great city of Alexandria about 250 B.C. by a group of seventy rabbis, who supposedly did their translations independently and when they were brought together all were found to be identical, convincing many of their inspiration (The Catholic Bible: Personal Study Edition, p. 217). The translations may have taken decades but what is clear is that this was the Bible of the Jews in the Diaspora and it was the Bible quoted by Jesus and the Apostles in the New Testament in 300 of 350 instances where the Old Testament was quoted. The other 50 are usually paraphrases of either the Hebrew or the Greek only. Moreover, it is important to note that at least the Ethiopian Jews, followed a different canon, which is identical to the Septuagint and includes the seven deuterocanonical books (cf. Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 6, p. 1147).

The early Christians used the Septuagint to evangelize the world and one of the most startling examples is the reference to the story of the heroic mother who was martyred after watching her seven sons tortured and put to death by a brutal king who tried to force them eat swine’s flesh in violation of Jewish law. This story from 2 Macabees 7 is cited in Hebrews 11: 35 and this is obvious from the fact that no comparable story can be found in the Massoretic Text (MT), which became the Protestant Old Testament. This is but one of a number of clear references to the deuterocanonical books in the New Testament. The Early Church Fathers likewise used the deuterocanonicals.

As Protestant scholar J.N.D. Kelly notes, “Quotations from Wisdom, for example, occur in 1 Clement and Barnabas. . . Polycarp cites Tobit, and the Didache [cites] Ecclesiasticus. Irenaeus refers to Wisdom, the History of Susannah, Bel and the Dragon [i.e., the deuterocanonical portions of Daniel], and Baruch. The use made of the Apocrypha by Early Church Fathers like Tertullian, Hippolytus, Cyprian and Clement of Alexandria is too frequent for detailed references to be necessary" (Early Christian Doctrines, 53-54).

Origen’s famous Hexapla consisted of six parallel columns which contained:

(1) the Hebrew of his day;

(2) the Hebrew text transliterated into Greek;

(3) Aquila revised Septuagint;

(4) Symmachus revised Septuagint;

(5) LXX (Septuagint)

(6) Theodotion (a revision of the Greek text of the Septuagint)

Unfortunately, it is no longer extant, but it shows that Origen, who headed the great Catechetical School at Alexandria, took all the translations into account in his studies and considered the deutero-canonical books inspired. It is also important to note that there were considerable differences, for example, the Massoretic Text of Jeremiah was 2700 words shorter than the Septuagint and there are significant differences in the text of chapters 10 and 23. In Esther 107 of the 270 verses in the LXX find no parallel in the MT (Anchor Bible Dictionary).

The massive and scholarly Protestant Anchor Bible Dictionary after acknowledging that mainline Biblical scholars have used the Septuagint to correct corruptions in the MT and that it was translated from Hebrew texts “not necessarily translated from a text accessible to us,” notes:

A second reason western scholars especially specialists in Christianity, should consider the LXX, is that it was the Bible of the early Christian Church. It was not secondary to any other scripture; it was Scripture. When a writer allegedly urged his audience to consider that all scripture given by divine ‘inspiration’ is also profitable for doctrine, it was to the LXX not the Hebrew that attention was being called. The LXX also provides the context in which many of the lexical and theological concepts in the NT can best be explained. Excellent syntheses of the relationships between LXX and NT have been made. Summaries and evaluations of these discussions and issues appear in Smith (1972 and 1988).

Martin Luther wrote in his commentary on John, “We are compelled to concede to the Papists that they have the word of God, that we received it from them, and that without them we should have no knowledge of it at all." Luther’s embrace of the so-called Palestinian canon was no doubt also driven by his new-found theology. Just as the Jews found the Messianic texts unpalatable, so too the reformers had their theology-driven agenda. Luther reject the Macabees because 2 Macabees 12:45-46 contradicted his denial of Purgatory when it says “...it was a holy and pious thought...” to make “...atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin.” This clearly shows the Jews believed in praying for the dead and suggests the dead might be purified of their sins, lending credence to the doctrine of purgatory which Luther had rejected.

Perhaps we should conclude by remembering history, which tells us that not all Christians agreed on what was in fact inspired Scripture. Scriptural books were denounced by some as spurious and books that had no divine inspiration were sometimes considered to be inspired. Thus, it was and is critical to have an infallible authority to settle the canon of Scripture. This is the rationale for the councils of Hippo, Carthage and Rome addressing the canon issue. The canon of both the Old and New Testaments, was finally settled at the Council of Rome in 382, under the authority of Pope Damasus I. It had been used in the Old Itala or Vetus Itala, Latin Bible in use until the Vulgate of St. Jerome was published in 405 A.D.

Numerous Church Councils reaffirmed the Canon and it was not challenged until Luther’s actions in the Reformation. Catholics did not change the canon of Scripture to fit their theology but the Reformers did. It is well to remember that the Protestant myth that the Catholic Church supposedly added seven books to the Canon at the Council of Trent is still around and needs to be corrected by people who take the time and the trouble to examine the historical record. This is not difficult to do. Please examine your traditions to see if they are of men or of God. This is an essential distinction!

Need more convincing? Check out the writings of the Early Church Fathers on this topic by Clicking Here.