The writings of the first century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, who was employed by the Romans to write The Jewish War and was also the author of the work entitled, The Antiquities of the Jews, support the account of the life of Christ on a number of important points. All the extant manuscripts of the Josephus work on the Antiquities of the Jews contain a passage which discusses the life, miracles, crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior. Though Josephus was not a Christian he shows Jesus to be something more than a man. For example in this passage translated by the noted scholar of Josephus, H. St. John Thackeray, he writes:

Now about this time arises Jesus, a wise man. If indeed he should be called a man. For he was a doer of marvellous deeds, a teacher of men who receives the truth with pleasure: and won over to himself many Jews and many of the Greeks (nation). He was the Christ. And when, on the indictment of the principal men among us, Pilate had sentenced him to the cross, those who had loved (or perhaps rather 'been content with') him at the first did not cease: for he appeared to them on the third day alive again, the divine prophets having (fore)told these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And even now the tribe of Christians, named after him, is not extinct.

This passage is found only in the Slavonic or Old Russian translation that was first edited and published in 1906. Jewish scholar Robert Eisler presents a strong case, despite his anti-Christian animus and uncalled for theorizing that the Slavonic version was translated from an early version of the work, The Jewish War.

There are other important passage referring to Jesus in The Jewish War, including this one:

It was at this time that a man appeared--if "man" is the right word--who had all the attributes of a man but seemed to be something greater. His actions, certainly, were superhuman, for he worked such wonderful and amazing miracles that I for one cannot regard him as a man; yet in view of his likeness to ourselves I cannot regard him as an angel either. Everything that some hidden power enabled him to do he did by an authoritative word. Some people said that their first Lawgiver had risen from the dead and had effected many miraculous cures; others thought he was a messenger from heaven. However, in many ways he broke the Law--for instance, he did not observe the Sabbath in the traditional manner. At the same time his conduct was above reproach. He did not need to use his hands: a word sufficed to fulfill his every purpose.

Josephus continues:

Many of the common people flocked after him and followed his teaching. There was a wave of excited expectation that he would enable the Jewish tribes to throw off the Roman yoke. As a rule he was to be found opposite the City [Jerusalem] on the Mount of Olives, where also he healed the sick. He gathered around him 150 assistants and masses of followers. When they saw his ability to do whatever he wished by a word, they told him they wanted him to enter the City, destroy the Roman troops, and make himself king, but he took no notice . . . . When the crowds grew bigger than ever, he earned by his actions an incomparable reputation. The exponents of the Law were mad with jealousy, and gave Pilate 30 talents to have him executed [sic]. Accepting the bribe, he gave them permission to carry out their wishes themselves. So they seized him and crucified him in defiance of all Jewish tradition . . . .

In the days of our pious fathers this curtain [of the Temple] was intact, but in our own generation it was a sorry sight, for it had been suddenly rent from top to bottom at the time when by bribery they had secured the execution of the benefactor of men--the one who by his actions proved that he was no mere man. Many other inspiring "signs" happened at the same moment. It is also stated that after his execution and entombment he disappeared entirely. Some people actually assert that he had risen; others retort that his friends stole him away. I for one cannot decide where the truth lies. A dead man cannot arise by his own power; but he might rise if aided by the prayer of another righteous man. Again, if an angel or other heavenly being, or God himself, takes human form to fulfill his purpose, and after living among men dies and is buried, he can rise again at will. Moreover, it is stated that he could not have been stolen away, as guards were posted around his tomb, 30 Romans and 1000 Jews.

While Josephus obviously got some of the details wrong, this historical testimony is a valuable addition to the Gospels themselves and the writings of the Early Church Fathers. These quotations can be found in Thackeray's book Josephus on pages 129-131, 141-142 and 144-146. A good discussion of these passages and their significance may be found in Warren H. Carrol's A History of Christendom, volume 1, The Founding of Christendom, pp. 296-297. Carrol concludes, "In light of these considerations, the Christian need not hesitate to proclaim the Incarnation a fact of history, as well attested as any other historic fact in ancient times, indeed better documented than most.

Carrol adds, "Some may doubt or deny the historical reality of the Incarnation, just as all human testimony, no matter how truthful or well substantiated, may be doubted or denied by members of a fallen [sinful] race. But by all normal standards of historical judgment on sources and evidence the Incarnation is a fact, and would unquestionably be almost universally recognized as such if existing testimony and evidence referred o any morally and spiritually neutral even reported for this period."

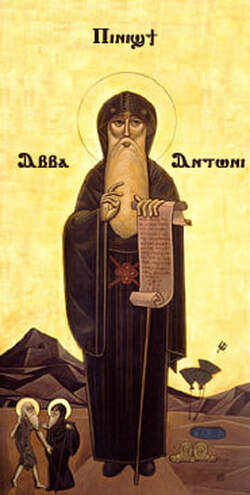

St. Antony of the Desert and African and Eastern Monasticism

The Ascetic movement produced a new icon of ideal Christian life, the monk or ascetic. This movement began earlier as various Christians lived ascetical lives in a severe way, with much self-denial and mortification. The founder of Western monasticism is St. Anthony (Antony) of Egypt (250-356), the first Christian hermit. As a young man he was converted to a radical following of Christ. He gave up his family wealth and eventually (age 35 yrs.) went to live in an old fort in the desert. He is often referred to as St. Antony of the Desert as a result.

He felt he had to escape the sin of the city. He had already led an ascetical life and studied other ascetics. By 305 A.D. curiosity seekers went out to find him and found he was aglow with spiritual joy, leading many to follow his way (but he only agreed to be their spiritual guide after years of this). He is the father of eremitical monasticism. He was 54 years old at the time he founded his monastery with scattered cells.

His Life by St. Athanasius says that Satan tortured him with temptations including boredom, laziness and the phantoms of women, but he overcame these with intense prayer. The devil harassed him with images of demons in the form of wild beasts who inflicted blows on him. He lived for 20 years in an old Roman fort in the desert and kind people fed him by throwing food over the wall. He refused to see anyone, but a colony of ascetics formed around him on the mountain, who wanted him to be their spiritual guide. He spent 5 or 6 years instructing them and organizing them before withdrawing to the solitary desert again.

On only two occasions he went to Alexandria, once to strengthen Christian martyrs in the persecution of 311 at the age of 60 years old (expecting to be martyred himself) and once to preach against the Arians near the end of his life when he was 88 years old (d. 356). He died at the age of 105 years old in 356 or 357 according to St. Jerome. In his humility after living 45 years in the desert, he requested his grave be kept secret so that people would not come out to it and reverence him. To this day, his rule for monks, which may have been written up by one of his monks, is followed in Syria and Armenia.

The word monk comes from the Gr. monos, which means literally, one or alone. Later another Egyptian, St. Pachomius, founded communal monasticism (substituting the cenobitical or communal life for the eremitical one). He was born in 286 and had an ascetic master, Palemon, and about 320 A.D., he founded a community of ascetics near Tabenna (Tabennisi) and attracted many followers (eventually 7000 who spend time alone in prayer but gathered in community for meals, liturgy, and sometimes for special celebrations). He refused the priesthood when St. Athanasius offered it to him. He died about 348 having brought together 7000 monks.

Monasticism became so popular that the population of the monasteries rivaled that of secular towns. One book was the Desert of Cities. The title reflects the exodus of people wanting to live in the desert. People wanted to live a radical expression of their faith (white martyrdom vs. former red martyrdom of blood). They devoted themselves to prayer and penance, spawning the religious life models that followed. These ascetics were celibates and they made celibacy an ideal in the religious mind—following the example of Christ. Later this became the norm for priests in the West and for bishops in the East. In his book, The Apostolic Origins of Priestly Celibacy, Fr. Christian Cochini argues that this emphasis on celibacy was not a new departure but rather a harkening back to the apostolic example. He cites, for example, canons of the Councils of Elvira (Spain) and Arles (314), which specifically prohibit marital relations of married clergy after ordination on penalty of being “deposed from the honor of the clergy” (p. 161).

The ascetic movement was also a great new source of evangelization and spirituality for the Church. It spawned a witness to Christ and heightened spirituality

RSS Feed

RSS Feed